Soundtracking: Lust for Life

by Zachary Davis, March 30, 2017

Being a movie snob during your middle school years is a difficult occupation; most of the cool films you wanted to see were restricted by the ratings system, and having to wait for the film to come out on VHS dulled the excitement a bit. I wanted to see films like Pulp Fiction and Trainspotting in the theater, but alas...I was 12 years old.

But hey—if I couldn’t see the movies, I could buy the soundtracks, dammit. As the music video culture of the 90s was influencing more and more filmmakers to take music from different sources to use, I knew that the filmmakers of these movies had chosen songs for very specific reasons, and even if I couldn’t see the reasons outright on celluloid, I could at least imagine them on my headphones.

“It’s kind of like I get to watch the movie! ….right?”

The music of Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting has since become as iconic as the film itself. Boyle has often been accused of choosing style over substance, and of turning a subject as heartbreaking and sorrowful as heroin addiction into a two-hour music video. But Boyle wouldn’t see much wrong with that. As Boyle has stated, we all live life inside of MTV now.

Music is a constant thing. It’s in our earbuds, it’s in the grocery store, it’s in the hospital elevator—there’s no escaping its pulse. It’s become so much a part of our lives, so intricately woven into the fabric of our present day as well as our memories, that separating it is almost an impossibility.

As Boyle explains, “pop music refreshes us, it completes us, it renews us.” And to be honest, while Trainspotting as a movie was a huge part of my life when it finally came out on VHS, I knew it as a soundtrack first.

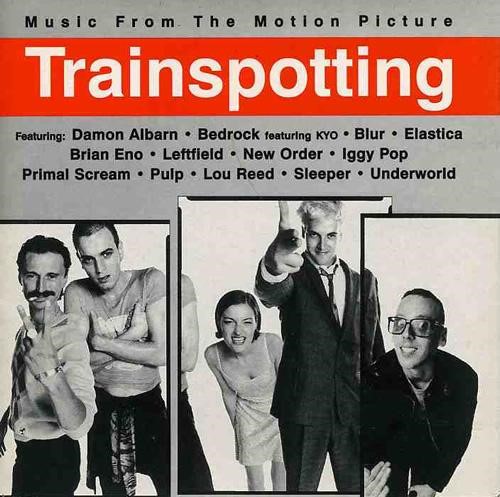

And what a soundtrack. Through it, I was introduced to my new favorite bands in 1996. Blur. Pulp. Elastica. Through them, Britpop became my new teenage angst. But it also introduced me to those artists that I really should have already known about, including Iggy Pop, Lou Reed, Brian Eno, and New Order. The soundtrack, very swiftly and very thoroughly, changed my life.

But to say that Boyle’s use of source music simply turns the film into a giant music video is a huge mistake; Boyle’s choices of music have a deeper significance. Let’s go ahead and push play on the old Walkman, and see what’s really behind the music.

“I am just a modern guy….”

1) Iggy Pop, "Lust for Life"

Right away, we are thrown into both the kinetic energy of the film itself, and the thesis statement of the film in general: the drug addicts in this film are escaping the banality of modern life through the ecstasy of heroin, and Boyle’s choice of music here also introduces his idea of using music to highlight characters’ experiences as well as for juxtaposition to highlight key points he is making.

Boyle is a big fan of using juxtaposition to make a point, and musical irony is one of his chief tools. Our introductions to Renton and his motley crew are shown through scenes of their “Ordinary World” of robbery and heroin usage. But it’s important to see how the music showcases Renton’s position—while yeah, heroin usage is depressing, it’s not miserable for the users...it is pure ecstasy, an alternative to the dull absurdity of modern life.

Why choose life when drugs are better? What does having a lust for actual life get you? Bills? Big-screen televisions? Human relationships? These cultural and societal norms don’t matter when you have a healthy drug addiction, and the movie plays on this not just with the up-tempo dance jangle of Pop’s tune, but also, the context of the tune itself.

Iggy Pop: known celebrity and retired heroin user singing about his former addiction with backing pop vocals. The idea of celebrity will play out in ways throughout the films, but with the lead track, the tempo of the film is set: a tempo that reflects the life and relationships of its characters. And it begins with Iggy Pop the Elder, who is nearly deified in the film and maintains a watchful eye on the junkie youth of Scotland throughout in the background, whether it be in posters on apartment walls, in conversation, or in other musical interludes.

Ah, the sheer beauty of toilet diving in Scotland for suppositories…

2) Brian Eno, "Deep Blue Day"

The musical irony used throughout the film is mostly employed when Renton’s point of view is front and center—he is the protagonist with the central conflict here after all: does he kick drugs and accept the poison of modern living, or does he stick with his poison of choice that keeps him in miserable ecstasy?

When Renton decides to kick his habit, the only thing keeping him from his goal is an unfortunate loss of suppositories. This beautifully atmospheric track from Brian Eno [another “classic” artist here] turns a dive down the “worst toilet in Scotland” into a beautiful swim through a deep blue sea.

The beauty of this blue day set against the toilet dive is meant to play for irony, but it is also meant to show us character motivation—Renton’s triumph here showcases his conflict against both sides of society. And emerging from the toilet becomes a sort of rebirth for our hero. This idea of beauty against ugliness comes out many times throughout the film—Reed’s “Perfect Day” narrative relocated to an overdose in dingy Scotland, for instance—but never more precise than this memorable moment.

3) Primal Scream, "Trainspotting"

“You’ve got it, and then you lose it, and it’s gone forever.”

For the first time on the official soundtrack, we are treated to our first “dance” song as Renton and Sick Boy talk about how age gives way to a loss of talent; Primal Scream’s jazzy electronic music perfectly illustrates this point; as rock and Britpop were leaving the clubs of Europe, dance music from acts like Primal Scream [who previously had been a rock / Britpop outfit] were coming up. Boyle has stated that Trainspotting is also about the changing of the guards within cultural landscapes, and Primal Scream’s beats playing lightly over Renton and Sick Boy’s discussion, as though it were listening in, captures their point: David Bowie and Lou Reed may be going out with age, but new acts are waiting in the wings, and that’s just how it goes. Culture and society may change, but heroin users can float through it, unscathed.

In both the novel and the film, the landscape of music is changing as the characters remain stagnant. It also hints at another running theme of the film—the status of Scotland within the United Kingdom is absolute “shite.” Sure, they let Sean Connery become a part of the British bourgeois with his James Bond films….but isn’t it all just another form of colonization? There may not be a point to rebelling against a colony of wankers, but taking out some aggression with a BB gun may at least help; after all, isn’t hunting the ideal bourgeois activity of the English elite? Why shouldn’t the colonized Scottish have their own bit of fun?

Speaking of…

4) Sleeper, "Atomic"

“Tonight—make me tonight….”

Danny Boyle uses music not only for irony’s sake, but also to connect us more to the plights and personalities of his characters. As the gang goes out for the fleeting social bourgeois scene of nightclubbing, Boyle shows us the frustration and fleeting connections of sexual pursuit for the youths.

This pursuit is scored to the euphoria of dance-hit “Atomic” [covered by Sleeper, but done originally by the original punk-rock-girlfriend-everyone-wanted Blondie]. From the 70s vibe of Iggy Pop and Brian Eno, this song continues the musical evolution into the 80s. The sexualized lyrics and rhythm of the song also underscore Renton’s attempt at initiating his own sexual conquest, which culminates in the meeting with one jaded club goer [Kelly MacDonald], whom he feels an immediate connection with.

Boyle further uses the song to tie together the sexual pursuits of three characters: Spud’s failed sexual exploit when he passes out, Tommy’s panic over a lost sex tape, and Renton’s “goal” of sex with Diane. The montage of these three moments reveals their lives behind closed doors, while also showing us something meaningful about each of the characters. These may be depraved drug addicts, but this is the closest [and perhaps most human] moment we get with them before it all goes down the drain.

5) New Order, "Temptation"

“And I’ve never met anyone quite like you before….”

The second song with this title [Heaven 17’s song also played in the club the night before], this song becomes a sort of motif with Renton’s illegal relationship with Diane; she is singing it in the shower after Renton’s affair with her, and it will also be the song she sings during Renton’s cold turkey nightmare later in the film. Also, having it play while Renton shares an uncomfortable breakfast with Diane’s parents and learns of her age makes a strange situation that much stranger.

The music also seems to mislead the audience and play with expectations—Diane’s parents listening to New Order may make them her roommates….until she shows up in her school uniform. Irony is at play again, and having this song play in the background [and show up later] underscores the unease that comes with Diane’s revelation.

6) Iggy Pop, "Nightclubbing"

“We’re nightclubbing….we walk like a ghost….”

Having chosen life, and not getting much satisfaction from it, Renton makes the informed decision to get back into heroin. Getting back into heroin, however, is a full time business, and Renton’s efforts to pay for his addiction are given sinister intentions thanks to Iggy Pop’s slinking dystopian dance hymn.

Danny Boyle references Iggy Pop again here for a different reason: Tommy, devoted Iggy fan, also tries heroin here [even referencing the “Iggy Pop” thing as another reason for his recent breakup]. Renton is resistant to embroil him in heroin’s grasp, but once Tommy offers money, there is no stopping it. Tommy, as the one pure “normal” member of the gang until then, has a tragic resonance that will echo throughout the film until his death in the third act.

“So what’s the worth in all of this….?”

7) Blur, "Sing"

Britpop was a pretty interesting beast during the mid-90s, as it was essentially just alternative rock with a distinctly British attitude. Boyle’s inclusion of Britpop in the movie signifies a few interesting things, but mostly, it shows how the musical landscape was changing through new music scenes and social labels. The kings of the Britpop scene were Blur, and “Sing” appears just after the death of Baby Dawn and right before Renton hits his personal low point.

The lyrics point to a loss of innocence, and its position in the film certainly confirms its point: Renton understands the loss that accompanies the crushing cycle of heroin addiction, how it becomes necessary to “pile misery upon misery” to maintain the ecstasy of the high long after it has faded. To maintain the high, it becomes necessary to fall into a cycle that seems without end and without redemption.

The death of Baby Dawn and the imprisonment of Spud signal a fall from innocence. Even though Renton avoids jail time, a redemption set to the melancholy piano and choral voices of Blur’s song, he is still imprisoned by his choice of poison. The steady drumbeat underneath the song points this out—time goes on, cycles repeat, and life without a hit is just another “long hard day.”

The lyrical reminder that “the child is dead….” don’t much help Renton’s position, and the fact that the mention of “the child in your head” may reference the lost innocence of Renton, but it also foreshadows the withdrawal nightmare awaiting Renton’s long hard fall…

“You’re going to reap just what you sow….”

8) Lou Reed, "Perfect Day"

Boyle again chooses music from a celebrity heroin user [and rock elder] with Lou Reed’s “Perfect Day.” The song itself details drinking sangria in the park, visiting the zoo, and spending time with a loved one that cares for you. Boyle employs musical irony again by showcasing not a day in the park, but dingy uncaring Scotland, and uses this setting to show us a very un-perfect day for Renton: overdosing in the heroin den, being dragged down steps, head hitting concrete, laid out in the middle of the street, tossed into a cab without much regard for his life or death, and dumped off in front of a hospital. The song itself is beautiful, and playing it against one of the uglier moments of the film highlights the irony of Renton’s situation: the satisfactory ecstasy of the high is juxtaposed against the ugly reality of everything else the world of an addict is made of: uncaring friends, robbery, death, the loss of loved ones, and the destruction of every artifice of society that isn’t about the high.

Irony is all about playing with audience expectation, and this is played with in other ways too—an ambulance passes by, making us think Mother Superior has called for the appropriate help, but a cab stops instead to make the anonymous trip to the ER. And of course, the arresting visual of Renton collapsing into red carpet, only to emerge, resurrected, in the hospital does the job of putting us directly into the protagonist’s experience. All of it is tied together with this song, which leads us headfirst into Act 3 and Renton’s nightmarish withdrawal.

9) Pulp, "Mile End"

“Oh, it’s a mess all right….”

After Renton’s withdrawal [scored to the incessant club beat of an Underworld song], he takes off to London to start life as one of the English bourgeois….not that it works out that way. Renton is still on the outside of society, and Begbie’s arrival underscores that.

The band played during a montage of life with Begbie is another seminal band of the Britpop movement: Pulp. Another theme of the film is Scotland’s existential crisis within the United Kingdom, and Boyle seems to purposefully use Britpop whenever this point is being made. Renton’s assimilation into English culture does not work out well, and the sarcastic song points out the humor in his failed attempt to join society.

Musical irony plays out inside the song as well, with a happy upbeat melody playing out over a description of the horrid living conditions of “Mile End.” The faux-tourism montage of cheery England that had played earlier is cut down to size with the perversion of an idealistic domestic life that occurs here for Renton, who may have cut out the poison of heroin, but is now stuck with the poison of modern living through the filter of psychotic [and untidy] Begbie.

“The hall of dangers—for what you dream of….”

10) Bedrock, "For What You Dream Of"

When Begbie wins big on a gamble, he and Renton partake in a trip out to the club, where Renton makes an observation on the society changing around him [a callback to Sick Boy’s theory while hunting in the park]. As Renton explains, “times are changing, music is changing, drugs are changing, men and women are changing….” Hell, society is hard to keep up with when your heroin addiction is now a forgone occurrence that leaves you wide-eyed and sober.

It’s hard for Begbie too, who fails to realize that his hook-up for this night is actually a man. Begbie too has difficulty living in these changing times where the danger of the unknown is now a facet of society. As Renton sees, life can be just as ironic when you’re off smack as when you’re on it.

11) Elastica, "2.1"

“Three’s the number….”

With the arrival of Sick Boy, Britpop shows up again with Elastica’s “2:1.” Besides the obvious reference here [it’s Begbie and Sick Boy against the single Renton], it becomes more obvious that Renton assimilating into English culture with two of his mates just won’t work; not even eating fish and chips in London is going to cut it.

It’s interesting to note here that anytime Britpop plays, besides commenting on assimilation into the English bourgeois, it also seems to be during a time when Renton’s point of view is overtaken by those around him, including aspects of the society he is set against. Blur plays when Renton is arrested, Pulp plays when Begbie takes over his flat, Elastica plays when Sick Boy sells his television….

On the other hand, when Renton’s experience and decisions are front and center, the music is more of the “classic” variety: Iggy Pop, Lou Reed, Brian Eno, New Order. It’s perhaps no coincidence that Britpop plays when Renton feels out of control of his situation, more “classic” rock plays when Renton is more in control, and the new-fangled electronic music plays when Renton appears to be attempting to initiate a change in his situation.

12) Leftfield, "A Final Hit"

“There’s final hits and final hits —what kind was this to be?

Electronic music here signals another attempt at change: the robbery that will make the gang rich. The use of the song here is fairly deliberate—it’s Renton’s final hit, after all. As the final member of the gang, Spud, shows up, Renton is nearly thrown right back into his old ways. A robbery provides a dangerous opportunity to see Renton get royally screwed [pun intended].

Will Renton go back into the heroin lifestyle? Will he be able to rid himself of his “friends,” toxic to his attempts to choose life? Will the poorly orchestrated plan to make out with cash go off?

There is tension but also prospect. Again, this new genre of music indicates change for Renton—he seems strong for perhaps the first time in the film, and it appears that he can make this hit final. His character has come full circle, while the landscape of music in the film has fully evolved.

13) Underworld, "Born Slippy"

“Are you on your way….to a new tension….?”

“Born Slippy” was the breakout hit of the film’s soundtrack, launching Underworld and dance music firmly out into mainstream culture. Iggy Pop’s career was resurrected as well thanks to the inclusion of “Lust for Life,” but Underworld was the big hit coming off the film’s release.

It’s used when Renton makes the final decision to commit to ultimate change and take the money already stolen from the robbery. Danny Boyle explains that this moment could have been played for tension, but instead, the driving beat and euphoric melody turns the moment into one of resolution and resolve. This is Renton’s decision to finally escape the empty culture of his prior life and become a member of society.

The music of the film and the character of Renton have fully evolved. Renton breaks out into mainstream society just as dance music would with this Underworld hit, and Renton’s new speech on choosing life is now about how he looks forward to a life of cultural consumerism….and why not? Everyone else seems to. Trainspotting has been about escaping life to experience ecstasy, and the song’s rhythms drive this point home, even as Renton’s grinning face blurs and the line between him and us, the rest of society, blurs along with it.

“I’m gonna be just like you.”

14) Damon Albarn, "Closet Romantic"

From Iggy Pop’s frenetic drums, to Blur singer Damon Albarn’s Britpop closer, the soundtrack covers the changing musical culture that exists behind Irvine Welsh’s novel. It also signifies the transition of Renton from junkie to English bourgeois. Albarn’s playful horns and nearly funhouse rhythms seem to satirize English nobility in the instrumentation and create a comic effect, which sort of makes sense when you look at Renton’s resolution—he wants to be another cog in the societal machine because that is the new high he needs. Assimilation into normal culture is not seen as being bad, necessarily, but there is a sardonic kind of juxtaposition being made here as well—isn’t being part of the cultural program just another way to be drugged?

The recitation of James Bond titles [featuring Scottish Sean Connery] during this song [it's only lyrics] indicate this idea as well—Renton is choosing a life where he is assimilated into English bourgeois culture—he has forsaken one poison for another. And is this the biggest irony? Isn’t the modern culture Renton has mentioned—the “normal” culture of the consumer middle class—itself a drug? “Job, family, the fucking big television”... these are all the drugs of modern convenience that Renton is accepting.

As Renton glides into an oblivion of bourgeois convention, we are left with the the slightly sarcastic tune [from a Britpop artist, of course] that plays on this notion—when you are forced to live an existential crisis, what really is the right mode of living? Choosing life is, as Renton indicates, going with the changes, “getting by, looking ahead, the day you die.”

The soundtrack itself works to showcase this change. Boyle is not just concerned with style; he is concerned with telling a story with multiple aspects. The music he uses highlights juxtaposition, character motivations, humanity, tonal abstractions, and themes that run the gamut from choosing life to Scottish assimilation into colonized culture. Most importantly, Boyle uses music to tell the story he wants to tell, and this is what makes it endure. The fact that it’s also a collection of killer songs doesn’t hurt either.